–

Phil Turnball

Assistant Fisheries Officer

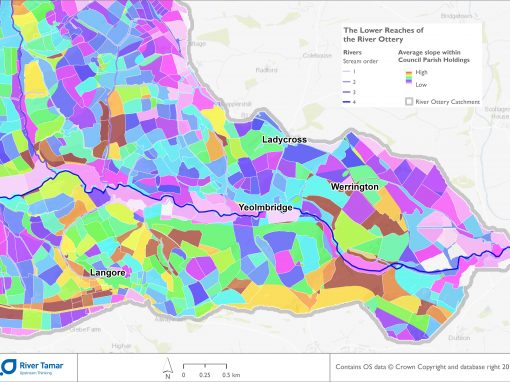

A few more months have now passed since I finished the survey season, after which I was awarded a brief moment to catch my breath. It didn’t last long. To my left was a pile of data in need of organising and interpreting, and on my right a series of tasks with deadlines. You may expect me to sit here and cry “Woe! Woe is me!”, but if that were the case then I’d be in the wrong job. The reality is all that fishy data reawakens a type of childhood excitement, for buried deep within lies valuable information, answers, and mysteries begging to be explored. Piece by piece, pictures started to appear (including both metaphorical ones and pretty GIS maps), combining to produce an understanding of what is happening within North West Devon river catchments.

Collecting data is a glamorous job, often inciting friendly comments from passers-by, for example “Cor, not a bad job, eh?”, “some of us work for a living, y’know”, and “not a bad way to earn your money, eh lad”. However, it’s the less glamorous, often unseen world of analysis and reporting where all that galivanting around the countryside begins to pay off. The countryside is pretty big, consisting of a lot of land being constantly worked, and therefore providing many avenues for impacts on West Country rivers. Tackling potential problems is a daunting task when the scale of each catchment is considered. Therefore, the data collected quickly becomes infinitely valuable in directing where and how the available resources are applied for maximum effect with maximum efficiency. Report writing becomes the foundation of winter works, with the stunning vistas temporarily confined to computer desktop wallpapers.

But fret ye not, my days of enjoying lunch by the rivers are far from on hold! One of the tasks embedded in my right-hand pile was the delivery of practical habitat improvements. Armed with a chainsaw, some rope, a handful of pulleys, and willing helpers, I have been enjoying the opportunity to increase river habitat productivity on a local scale. Let me shed some light on the matter (significance of pun to become clear): Migratory salmonid species utilise shallow riffle areas for spawning, where eggs are laid in a small gravel excavation, fertilised, and buried, leaving behind a distinctively shaped gravel nest called a redd. Over the next few months the young fish hatch as alevins, feeding from a yolk sac while remaining in the redd. Once the yolk is consumed, the alevins emerge from the gravels as free swimming fry, and drop back into the gravel riffle for shelter and food. Light penetration on the shallow riffles is important to stimulate primary productivity, feeding into a complex food web, and resulting in an abundance of diatoms, macrophytes, invertebrates and fish. In a naturally functioning river system, the staggered process of tree growth, death, and regeneration, coupled with intense natural competition, creates a complex and diverse bankside plant community both in species and age, leading to a varied light regime throughout the channel. This process has historically been capitalised through selective harvesting of mature timber, producing constantly regenerating coppice along river banks.

However, due to changes in material demand, land management pressures and subsequent changes in riparian management, some river banks have become overgrown by mature trees and shrub vegetation, causing excessive shading of channels, and reduced growth from riparian marginal species. This results in less productivity, particularly in shallow habitat utilised by juvenile fish, decreasing the abundance of available food.

With sensitive and controlled selective coppicing, light is strategically reintroduced to the river channel to restore primary production, and therefore feed into the food web. Increasing light on vulnerable exposed banks can reduce risk of excessive erosion through stimulating low-level vegetation growth. Furthermore, the woody material gained from coppicing works can then be used to create woody debris structures to enhance instream habitat, feeding into the river ecosystem and providing cover for growing juvenile and adult fish.

And so, the life of this river officer continues to diversify, reflecting the nature of working in a dynamic environment.

Sitting, typing, slurping in some tea; documents and spreadsheets becoming reality

Here fish, there fish, many places few fish; building up a list of what to accomplish

Reporting, reporting, and a smidgen of analysis; working to the point of mental paralysis

Work load directed by data being applied; finding a bit of time to get back outside

The humming, popping, shredding of the chainsaws; In the frost, in the sun, and even as the rain pours

Still windless days causing bird life to sing; Snowdrops and daffodils showing signs of coming spring,

Sitting on the riverbank reflecting about the job; not a bad way to earn a few bob!

Other Westcountry River Stories