When you see one of our river restoration projects taking shape – whether it’s a new wetland habitat or natural flood management features – there’s an important step that happens long before the first spade goes in the ground. It’s called a Land Drainage Consent (LDC) and it’s a crucial part of how we work responsibly with our waterways.

Rivers don’t respect boundaries. Any work we do on a stream or river – even with the best intentions – can affect water flow, wildlife, and flood risk both upstream and downstream. That’s why any organisation or landowner planning to work on a watercourse needs formal permission through an LDC application. For smaller streams and ditches, we apply to the local county council or lead local flood authority. For larger rivers, the Environment Agency reviews our plans.

This isn’t just red tape – it’s about ensuring our conservation work benefits the whole catchment, not just one site.

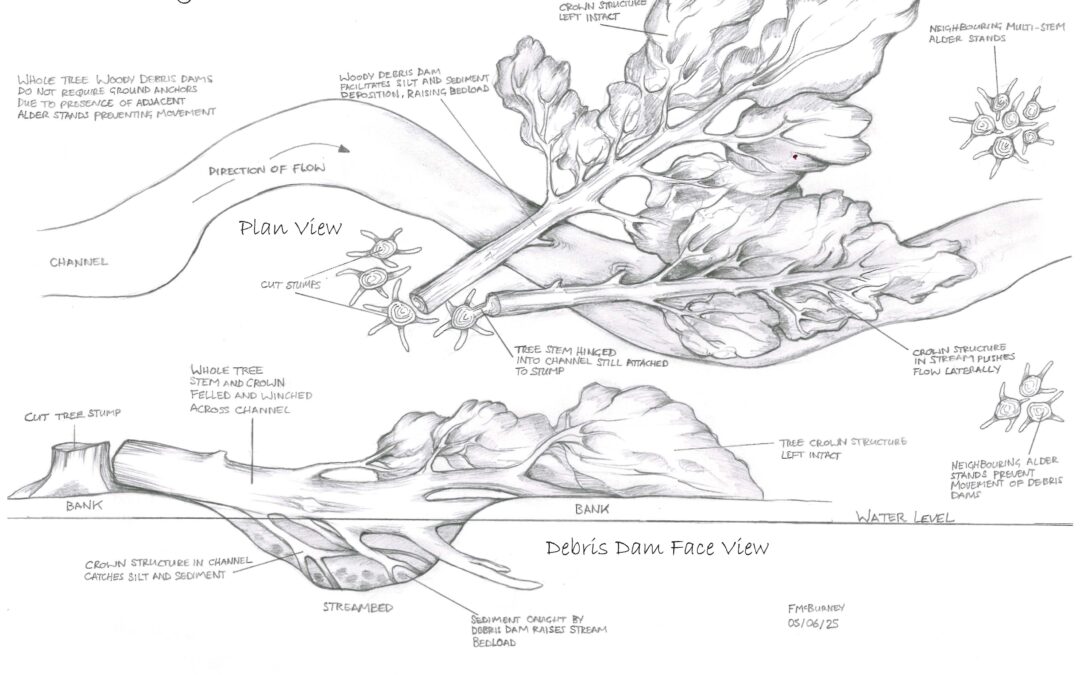

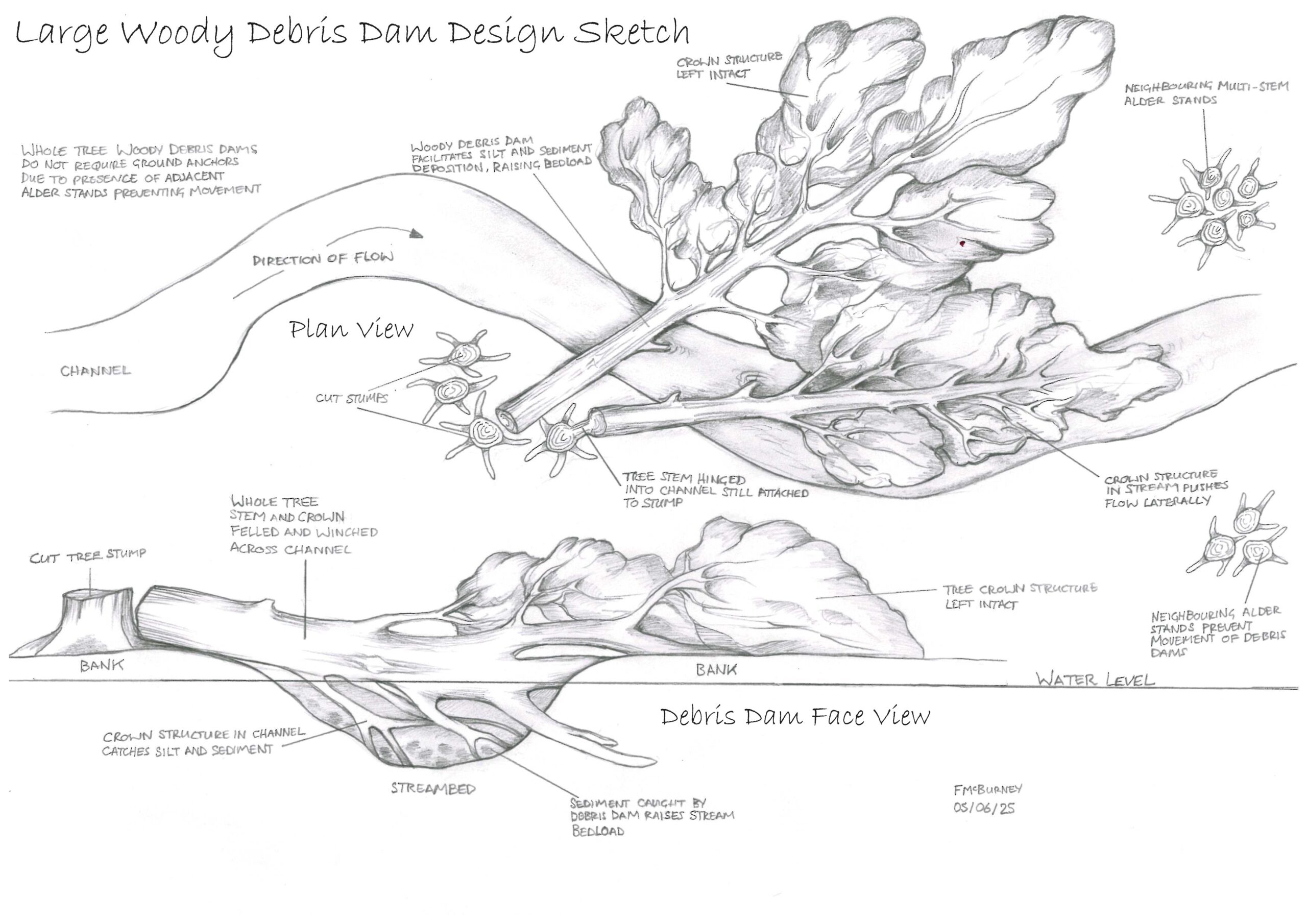

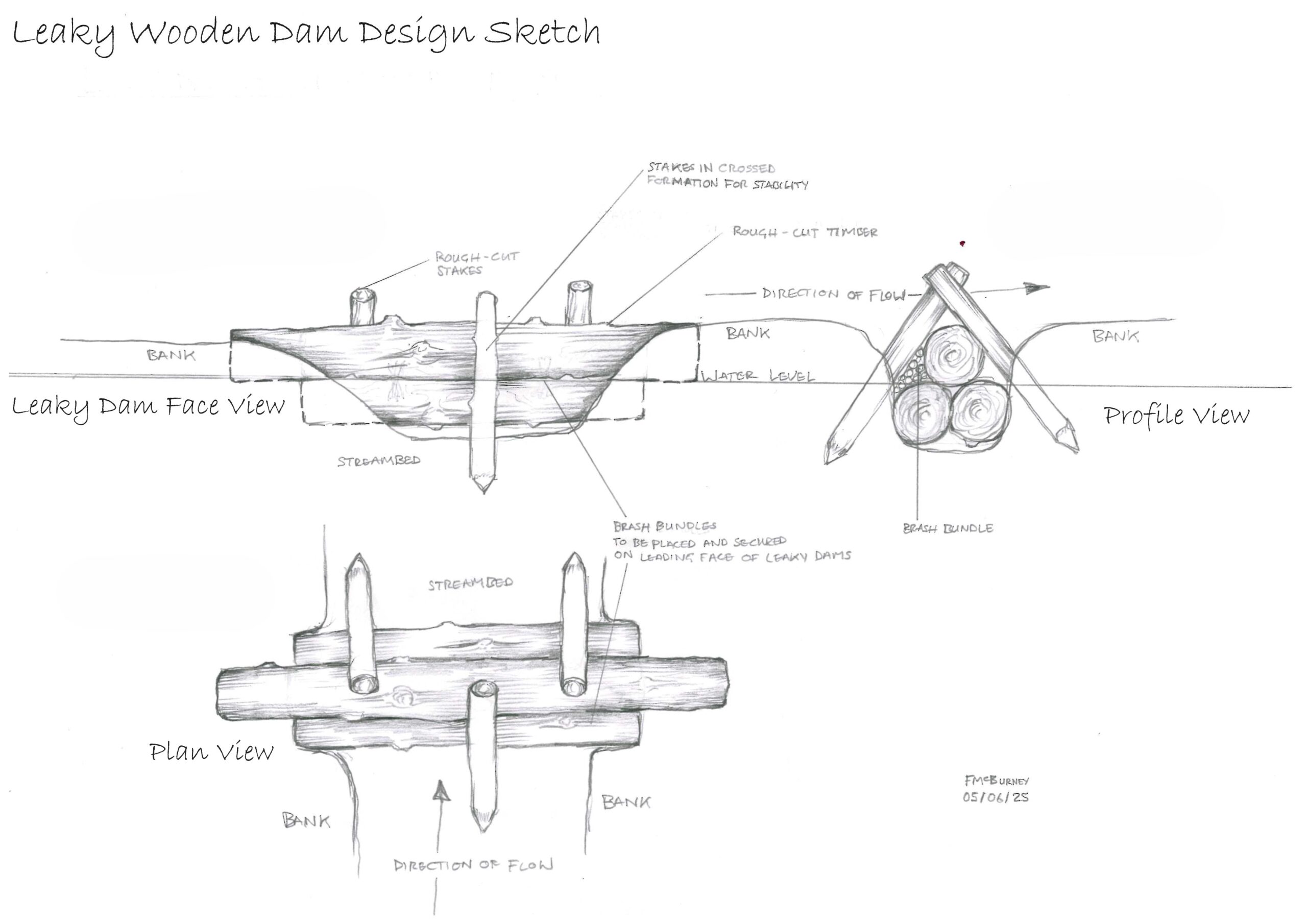

Many of our projects use nature-based solutions like large woody debris dams and leaky wooden dams – and these are exactly the kind of structures that need careful planning and approval. The wonderful drawings below show how these elegant, low-cost structures work with the river rather than against it. They were drawn by Fergus in our operations team for a recent Land Drainage Consent (LDC) application. They show beautifully how these elegant, low-cost structures work with the river rather than against it.

These dams are built from natural materials – logs, branches, and woody debris – arranged across or at an angle to the stream. Unlike solid barriers, they’re deliberately “leaky,” allowing water to flow through while creating multiple benefits:

For flood management: The structures slow down high flows during storms, spreading water across adjacent floodplains where it can be safely stored and absorbed rather than rushing downstream all at once to cause flooding in towns and villages.

For wildlife: The dams create varied water depths and flow speeds, providing different habitats for fish, invertebrates, and water plants. The woody material itself becomes home to countless insects and provides shelter for small fish.

For water quality: By reconnecting the river with its floodplain, the structures allow natural filtration processes to work. Sediment settles out, nutrients are absorbed by floodplain vegetation, and the river runs clearer.

Once permission is granted, what starts as lines on paper transforms into functioning habitats that benefit both people and wildlife. These structures are working examples of how we can manage water in ways that restore natural processes rather than fight against them.